ADAS stands for advanced driver assistance systems, a catch-all label for the electronic safety and convenience features that can help you react to traffic hazards, reduce workload on long drives, and (sometimes) step in when things go pear-shaped.

They’re not self-driving, and they’re not a substitute for paying attention. Think of ADAS as a second set of eyes and reflexes: useful, occasionally annoying, and only as good as the conditions they can 'see' in.

In plain terms, ADAS (advanced driver assistance systems) are technologies that support the driver by monitoring the road, other vehicles, pedestrians and lane markings, then providing warnings or interventions – usually gentle, but sometimes necessarily sudden.

Depending on the car and the brand, ADAS can include:

Some of these systems only warn you. Others can briefly brake or steer to help avoid a crash, or, if a collision is unavoidable, reduce its severity. Some motorists find them annoying, and certain new models do seem to overdo it on the 'beeps and bongs', leading one in five drivers to switch off ADAS – something ANCAP has acknowledged in a recent update to its 2026 evaluation criteria, mandating less annoying and intrusive safety systems. If you are buying a car based on how safe it is supposed to be, however, turning off any ADAS is counter-intuitive.

Image: The alert volume controls on a Hyundai Ioniq 5.

Most ADAS features rely on a mix of sensors and software.

These sensors feed data to the car’s computers, which interpret what’s happening around you in real time. If the system detects a risk (say, you’re closing on a stopped car too quickly), it can:

The important bit: ADAS are highly dependent on visibility and clear road markings. Heavy rain, fog, glare, dirty or foggy windscreens, faded lane lines, roadworks and bright sun low on the horizon can all reduce performance.

‘Auto cruise control’ usually means adaptive cruise control (ACC), not the old-school static speed version. It works by automatically slowing down or speeding up in response to the vehicle in front of you. Some advanced vehicles also adjust the speed of the vehicle on corners.

It’s one of the best everyday ADAS features when it’s well tuned – less ankle work on motorways, fewer accidental speed creep moments, and a calmer drive in flowing traffic.

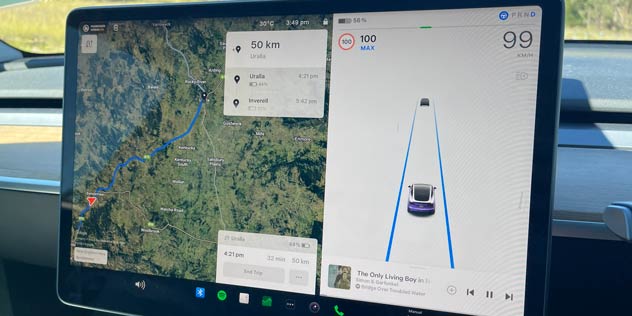

Image: Adaptive cruise control display on a Tesla Model Y.

Every brand does the button layout a little differently, but the basics of how to operate cruise control are pretty consistent:

Some carmakers, such as Tesla, incorporate activation into the indicator stalk or other interfaces, so check the car’s manual if you can’t see buttons mentioned above.

A simple rule: if the traffic is messy, cut-in heavy, or you’re in an area with lots of cyclists and pedestrians, it’s often better to drive manually. ACC is great, but it can be too polite (braking more than you would) or too optimistic (accelerating into a gap you wouldn’t choose).

Image: Traffic sensor display in a Zeekr 009

Lane departure warning (LDW) uses a forward-facing camera to look for lane markings. If you drift over a line without indicating, it warns you. Lane keeping assistance (LKA) goes one step further by applying gentle steering help (or sometimes selective braking) to guide you back toward the centre of the lane.

This is where driver preferences really matter. Some people love the subtle lane centring feel on the motorway. Others find it intrusive on narrow country roads. It typically works best on roads with clearly marked gutters, white lines or yellow edges. Most cars let you adjust sensitivity, warning type (beep vs vibration), and in some vehicles, whether it’s always on at startup.

A traffic sign recognition system typically uses a traffic sign camera (usually the same forward camera used for lane detection) to read speed signs and display them on the dash. In some cars, it can also link to cruise control, prompting you to adopt the detected limit or automatically matching it (depending on settings and local regulations).

It’s handy, but not flawless. Temporary roadwork signs, school zones, weather-related electronic signs, and partially obscured signs can confuse the system. Treat it as a reminder, not an authority.

A driver fatigue monitoring system goes by a few names: driver attention alert, drowsiness detection, or vigilance monitoring.

Some systems look at steering inputs and lane position, watching for 'wandering' behaviour. Others use an in-cabin camera to track eye movement and head position. If it detects patterns consistent with fatigue, you’ll get a warning to take a break.

It’s useful as a nudge, especially on long highway slogs. But it can also trigger after lots of tight corners (where steering inputs look 'odd') or if lane markings are poor. Either way, the message is solid: if you’re tired, stop and reset.

Blind-spot monitoring is one of the most appreciated ADAS features for a good reason: it covers the area your mirrors can’t. Typically, radar sensors in the rear bumper watch adjacent lanes and trigger a warning light in the mirror (and sometimes an alert if you indicate towards an occupied lane).

If your car didn’t come with it, you might be looking at a blind spot system aftermarket kit. These do exist, and they range from basic mirror-mounted warning lights to more complex radar-based solutions.

A few practical cautions before you buy:

If you’re considering aftermarket, look for reputable brands, clear local support, and installers who have experience installing third-party blind spot system units.

Yes, many manual transmission cars do have cruise control, and some even offer adaptive cruise control. But there are a few quirks.

Traditional cruise control in a manual usually cancels if you press the clutch or brake, which prevents the engine from over-revving. Adaptive cruise in a manual can be more limited: some systems won’t operate below certain speeds, and stop-start traffic functions may be unavailable because the car can’t change gears for you.

If you’re shopping for a manual and cruise control is a must-have, check the spec sheet carefully and, ideally, test it on a drive. Manuals are becoming rarer, and the driver assistance feature set can differ significantly between trims.

Here’s the part most people rarely think about: ADAS calibration and maintenance.

As mentioned above, ADAS work best when sensors are clean and uncovered. Some vehicles may warn you when their cameras and sensors need some attention, but just in case, make sure you give them a clean and dry when washing your car.

Because systems like AEB, lane keeping and adaptive cruise control rely on cameras and radar aligned to very precise angles, they often need calibration after:

Calibration can be static (done in a workshop with targets and measuring tools) or dynamic (a guided drive where the car relearns references). Skipping it can mean the system works poorly, throws error messages, or behaves unpredictably.

If you’ve had bodywork done, it’s worth asking the repairer explicitly: was ADAS calibration completed, and can they document it?

ADAS can make driving safer and less tiring, and in the best implementations it feels like the car is quietly backing you up. But it’s not magic. Sensors can be blocked, software can misread the scene, and the system might react differently to how you would.

Use ADAS as support, keep your windscreen and sensors clean, stay alert to warning messages, and don’t ignore calibration after repairs. The tech is there to help, but you’re still the one in charge.